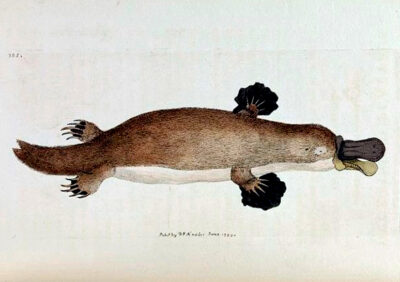

Finding some spare parts left over on the workshop floor, he decided to unite rather than waste them.”īut then Dawkins delivers the scientific punch line: a lucid explanation of the platypus’s remarkable ability, embedded in its goofy Donald Duck appendage, to detect the faintest electrical signals generated by muscular twitches of shrimp and other prey buried in the mud. Others have wondered whether God was having a bad day when he created the platypus. “It seemed so weird when first discovered,” Dawkins writes, “that a specimen sent to a museum was thought to be a hoax: bits of mammal and bits of bird stitched together. “I think it would have been twee.”ĭawkins begins one chapter of the book with a witty and erudite introduction to the platypus, an animal renowned for the ducklike bill grafted onto its mammalian body. “I just wouldn’t have felt comfortable saying, ‘I am a duckbilled platypus, and this is how I find my shrimps,’ ” he had said. About 10 minutes into an interview, as he sat in the airy living room of his Oxford home, casually attired in a T-shirt with a dinosaur emblazoned on its front and in midtalk about The Ancestor’s Tale, his book about evolution that some regard as his magnum opus, Dawkins had suddenly interrupted the conversation, risen to his feet, and stalked off to look up a very British word he had just used.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)